Less as more: decomputing in the age of tech accelerationism

By Bianca Wylie

In 2021, in the Journal of Social Computing, historian Jonnie Penn made the argument for “Algorithmic Silence: A Call to Decomputerize.” As he summarizes:

“Tech critics become technocrats when they overlook the daunting administrative density of a digital-first society. The author implores critics to reject structural dependencies on digital tools rather than naturalize their integration through critique and reform. At stake is the degree to which citizens must defer to unelected experts to navigate such density. Democracy dies in the darkness of sysadmin”[1].

In the current confusion about what sovereignty means, there is an ascendant and erroneous idea that it means funding the Canadian tech sector. Within this political framing, there is scant time allotted to questioning the foundational assumption that more technology, or Canadian copies of it, are beneficial for sovereignty, or beneficial at all. Piling ever more amounts of new computing systems into our lives can be dangerous in the context of equity, democracy, accountability, and environmental impact, as many in Canada have documented[2].

But working towards less and better, rather than more and faster, will be challenging. There is a tangled mess of long-standing incentives and norms that make it difficult to pull back on tech accelerationism. The idea that new is inherently good, or that technology will save us from climate collapse, are two examples. Rather than being singularly consumed by novelty, shifting more policy focus to maintenance and repair offers much in terms of resilience in the face of geopolitical instability.

The persistence of silos – technology and otherwise

In the 2010s, the open data movement shed new light on government technology systems. The conversations were about silos, silos everywhere, and the challenges this created for data sharing and better policymaking. Open data was put forward as part of the solution. Anecdotally, it has been said that the largest beneficiary of the open data movement was government itself, as ministries and divisions created new ways to see into each other’s data and operations.

Reduction/Reflection" by visiophone is licensed under CC BY 2.0

There are, of course, very good reasons for silos. And good reasons why governments can only use data for specified purposes. But there are fewer good reasons for the cartel-like information technology silos that ensure both never-ending growth of digital infrastructure, but also endless amounts of over-engineering and digital complexity. There is little incentive for IT managers to think about how to spend less or spend in concert with others in the same government. Budget and accountability structures often drive this situation.

Beyond the proliferation of independent digital infrastructure systems in the public sector, the general use of computer technology for administrative purposes and “modernization” has long been a supply-side push. In the 1960s, the famed sales team at IBM used to say that computers aren’t bought, they’re sold [3]. This, together with the leaking of technologies from the defense industry to the civilian world, the political desire to support domestic tech firms, exposure to endless “thought leadership” about innovation at both industry and government technology conferences, with a dash of Gartner hype, make for a heady mix. Together, they have created a rhetorical environment that makes it difficult to launch a political campaign for less new tech, and more repair and maintenance instead. But that campaign is needed.

There already is some friction that slows tech adoption in the public sector. Governments operate within a significant set of constraints: siloed departments, budget processes, onerous project management guidelines, and a range of compliance measures. These constraints aren’t going away, which makes it unlikely that things are going to drastically change due to any new flavour of technology product.

Digital public infrastructure, from building to maintenance

Though the hype around artificial intelligence (AI) shows no signs of slowing, the technology policy world is chanting more loudly about the ongoing importance of digital public infrastructure. Digital public infrastructure is publicly defined (not necessarily owned) and operated systems for data exchange, identity, and payment. One of the reasons it matters, as explained by Loïc Veza, Nisa Malli and Dan Monafu of the Canadian Digital Service, is “the potential [it offers] to reduce the cost of duplicate systems and duplicate information shared and stored in government systems”[4].

Digital public infrastructure is not new, nor is digital public infrastructure an inherently good public good. State power is state power is state power, and there are few cases where government infrastructure has been universally accessible, and fewer still where there weren’t major upheavals to some lives in service of the betterment and profit of others – railroads and energy being two of the most prominent [5]. These histories point to a need for equity and universal access to sit at the forefront of implementation, alongside a commitment to multi-channel service delivery, meaning that analogue options be available as well.

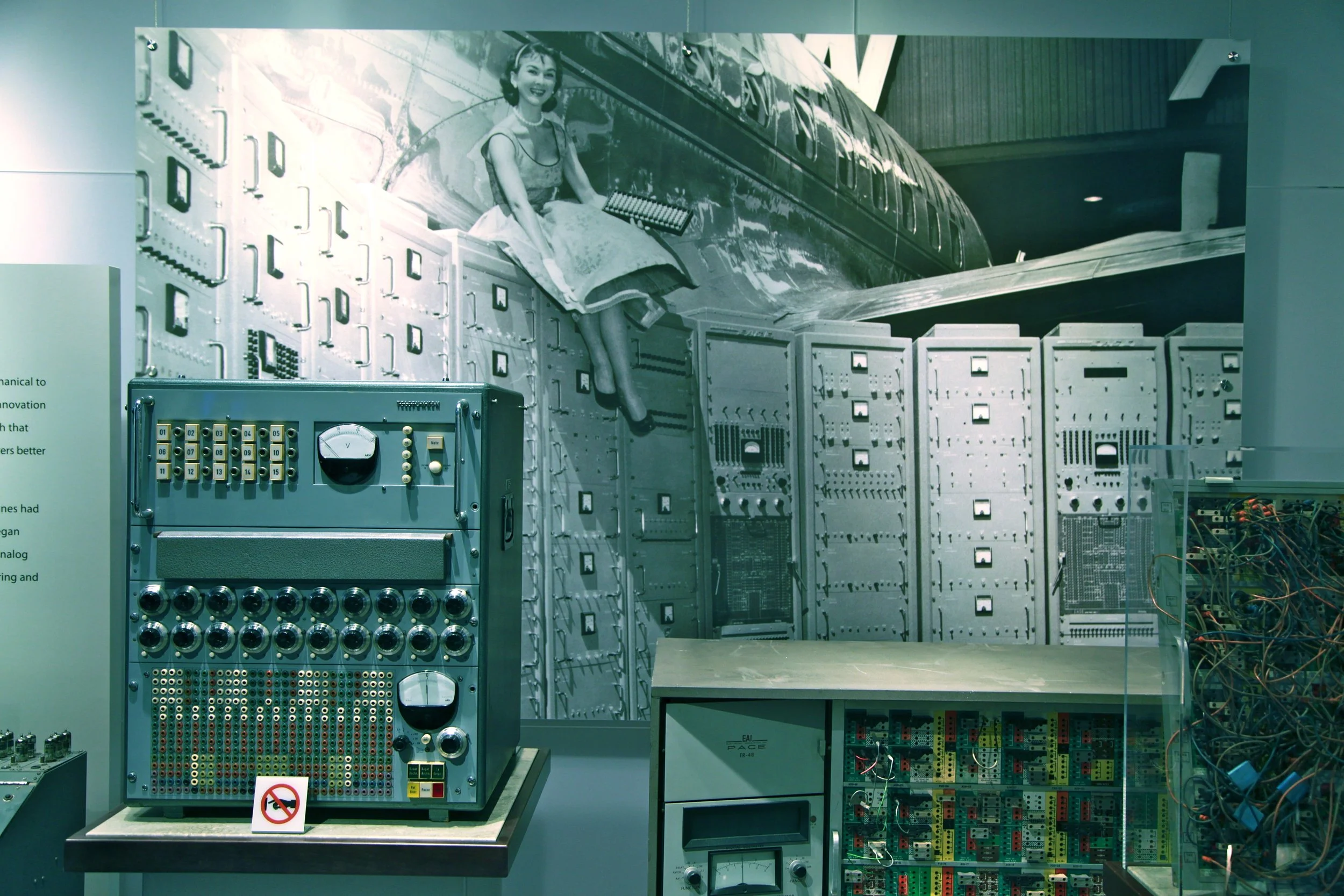

50 years old computer ad" by malfet_ is licensed under CC BY 2.0

When you speak to senior public servants that know their way around technology use in the government context, there is one theme you’ll hear time and again – a deficit in the maintenance of existing digital public infrastructure. One problem with the instinct to constantly buy more and build more is an immensely short-term focus, with little interest in the organizational and budgetary demands that go along with keeping digital infrastructure in good shape.

Estimates vary based on specifics, but making sure that at least twenty to thirty percent of the initial cost outlay for government technology is set aside for annual maintenance would begin to move things in the right direction. This also means that the allocated money has to be spent, rather than held in the name of deferred maintenance for the appearance of cost savings. Beyond this investment and expenditure, there are also changes that need to be made to job classifications and organizational design to support the necessary operations of good maintenance.

It will be interesting to see if and how the Government of Canada’s 2025 budget reorganization of capital and operating expenses might serve to make this problem better or worse. It is well-trod tech policy ground that governments work in projects not products[6]. This has negative effects on the public sector’s capacity to succeed with technology. A failure to invest in ongoing digital infrastructure maintenance, born of project-type funding cycles, can only end in failure. The big new information technology (IT) projects that auditor generals warn about are often doomed before they begin. They fail in large part because old systems are allowed to fall apart completely.

Deb Chachra, author of ‘How Infrastructure Works: Inside the Systems That Shape Our World’, wrote a piece in 2015 exploring the cultural norm of lionizing the building of new things [7]. When we do this we inherently reduce the value we assign to those that care for others – those that do the maintenance work in our world. Shannon Mattern, author of “The City is Not a Computer” expresses similar sentiments in a piece that explores the care and repair work done in a city[8]. She points to the lessons available to us for consideration within the context of digital infrastructure.

Decomputing allows for not only a shift to less stuff in general but also to a focus on taking better care of what we already have. Good for the environment, good for relationships, good for resilience. In addition, decomputing supports the prioritization of using tried and tested technologies, a major factor in large project success across all sectors of the economy[9].

Subtraction is not an instinct

The instinct to add rather than subtract when it comes to policy – or any kind of problem-solving – runs deep. In 2021, a paper published in Nature found that “people systematically default to searching for additive transformations, and consequently overlook subtractive transformations.”[10] The authors offer that this instinct, this norm, is particularly challenging when we are overburdened with excess information and complexity. In those contexts, it gets even harder to stop and think about the benefits of taking things away, of reducing complexity.

Diagrams from Xu Xinlu's Panzhu Suanfa (1573) for subtraction” by Jccsvq is licensed under CC 0 1.0

Rather than continually ante up in our building and buying, let’s explore the option of heeding Penn’s call for more algorithmic silence. As Dan McQuillan, author of “Resisting AI: An Anti-fascist Approach to Artificial Intelligence” suggests: “A pivot to decomputing is a way to reassert the value of situated knowledge and of context over scale”[11].

Louder than most tech policy conversations are ongoing concerns about trust in democracy and public institutions. This is an opportune time to invest in the people that make our systems work and sustain them over the long-term. In concert with addressing a range of other organizational design challenges that have been long-documented by scholars of public administration, such as interdisciplinary work teams and iterative policymaking, a different approach to quality over quantity offers much for the long-term, including the kind of digital infrastructure that is necessary, not nice-to-have, for any dreams of an equitable digital economy to be viable.

Bianca Wylie is a writer with a dual background in technology and public engagement. She is the founder of Time & Space Studios, a partner at Digital Public and a co-founder of Tech Reset Canada.

Endnotes

[1] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358336237_Algorithmic_Silence_A_Call_to_Decomputerize

[2] For example, see research and writing by: Blair Attard-Frost, Ana Brandusescu, Nathalie Diberardino, Mél Hogan, Cynthia Khoo, Rosel Kim, sava saheli singh, Christelle Tessono, Kristen Thomasen, and Ashleigh Weeden.

[3] Computer: a history of the information machine. Martin Campbell-Kelly and William Aspray. 2004.

[4] https://digital.canada.ca/2025/06/23/digital-public-infrastructure-dpi--powering-the-gcs-digital-future/

[5] Cowen, D. (2020). Following the infrastructures of empire: notes on cities, settler colonialism, and method. Urban Geography, 41(4), 469–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2019.1677990

[6] https://www.eatingpolicy.com/p/project-vs-product-funding

[7] https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/01/why-i-am-not-a-maker/384767/

[8] https://placesjournal.org/article/maintenance-and-care/?msclkid=7ef26afed03911eca225af3c1d3b52f0

[9]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364030703_How_Big_Things_Get_Done_The_Surprising_Factors_that_Determine_the_Fate_of_Every_Project_from_Home_Renovations_to_Space_Exploration_and_Everything_in_Between_Penguin_Random_House_2023

[10] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03380-y

[11] https://www.jrf.org.uk/ai-for-public-good/public-policymaking-from-ai-to-decomputing